When Kristin Burke — also a longtime GFY reader and author of the costume design site Frocktalk — invited us to give Fug Nation an inside peek at Sleepy Hollow’s Wilmington, N.C., set and dish wardrobe strategies with her, we jumped at it. The following post is NOT sponsored, nor paid for in any way except by our own wallets. And there are no spoilers for tonight’s season finale. The slideshow contains photos of the Regular Joe clothes Ichabod (likely) will never wear, his coats, tidbits from special-effects makeup, and scenes from the costume department; for Abbie’s stuff, shots from the set, an interviewer with Tom Mison’s set costumer, and anything potentially spoiler-y, check out Part 2 tomorrow.

WILMINGTON, N.C. – “I need to talk to you about the Latex Twins.”

It’s early days in the shoot for the two-part, two-hour Sleepy Hollow finale, and costume designer Kristin Burke is standing in the special-effects makeup trailer underneath a shelf holding rubberized molds of actor John Cho’s head gazing in lifeless, fleshy monochrome into middle-distance. Burke and Corey Castellano, the makeup department head who manages effects, are discussing a zany character concoction for which they have to make two featureless people look as if they’ve melted into each other and are slowly being pulled apart.

Conversations like this seem typical on the set of Sleepy Hollow, the FOX show that ostensibly resurrected the Headless Horseman legend but then expanded it to include the threat of a Biblical apocalypse, purgatory, horned demons, and other creatures of myth that harass the displaced eighteenth-century soldier Ichabod Crane and his modern-day cohorts. The show gets accolades for the sharply funny man-out-of-time gags and the charms of its cast, but the haunting production design of the show — from sets to makeup to costumes to special effects — are the unsung aspects that really sell it.

Using manpower to execute these visions, rather than computers, is also the norm here: Moloch, the horned demon engineering the charge toward the apocalypse, is a guy in a suit, as was a Golem, a creepy tree-person, the Sandman, and other things that go bump in the night. The Latex Twins were conceived by the writing staff, based on a photograph of two figures sitting on the ground, back-to-back, their heads yoked with a gooey plasma-like substance. (Like stepping on a piece of fresh gum, then slowly lifting your shoe off the pavement, except without the associated expletives. Well, there may have been; we weren’t there for that part.) After some debate about logistics, Burke and Castellano settle on dressing the actors in stretchy body-stocking-style Morph Suits, using panty-hose sprayed with special substance to harden it and give it that shiny, sticky effect, simulated the shared, stretched tissue. The duo opts to assemble the pieces ahead of time and then sew them into place on the day, in the moment, on the actors’ bodies. All for a passing two-second shot, probably a camera pan through a dark corner of purgatory, establishing its various horrors. It’s a long way to go for atmospherics.

But Sleepy Hollow is undaunted by the long way, and in fact, the long way seems to be the main way. The show is so visually ambitious that, in order to deliver on time, it often shoots with two units at a time — meaning, the episode’s director is working at one location, and another full crew is someplace else. One shot we watched, in a wooded part of Wilmington whose eeriness was enhanced by the show’s omnipresent mist machines, involved simulating an abrupt shift from bright outside light to darkness by having several crew members and a machine help raise and lower a giant tarp over the actress’s head for successive shots, something that also required constant adjusting to compensate for the sun’s constant motion. For another setup, an actor wakes up with Moloch looking over him/her. To achieve communicating this in extreme close-up with Moloch’s reflection in the actor’s pupil, they used the actual Moloch and a painstakingly nifty camera setup, rather than “fixing it in post,” so to speak. One scene with complex effects and a bloody visual gag took almost all day to shoot, and Burke’s team was overseeing fittings for a hundred or so extras for the following week.

It’s a crew of 450 strong (more than three-quarters of them local), pulling very long days, experiencing the curse of being good at their jobs: Every day that they pull off the requirements of each new episode impressively quickly and on a tight budget, that crazy schedule suddenly seems reasonable, virtually guaranteeing they’ll have even tighter constraints next time. Even so, the crew was unfailingly pleasant, even before any of them knew two fools with a blog were on the scene, and Burke graciously spent two days letting us tag along with her. We’ve split our almost two-hour tape-recorded interview with Burke into two parts; tomorrow’s will include anything pertaining to tonight’s finale, so as not to risk ruining anything for anyone, and there will be a bonus Q&A with set costumer Julia Rusthoven, whose main focus there is, as we call it, is Touching Tom Mison. We hope you enjoy all this almost as much as she probably enjoys that job.

The Burke Q&A starts after the jump.

JESSICA: Let’s start with your background and what got you into costuming, before we dig into the show itself. What did you study in undergrad that got you here?

KRISTIN BURKE: I went to Northwestern. I have a degree in French and I have a degree in radio and television and film.

J: What was your first job in costumes?

KB: In my junior year of college, I went out to LA to do a summer internship, and I had interviewed with Columbia Tri-Star and they put me — this is so ridiculous — they put me as the assistant production coordinator on the movie Hudson Hawk. I was like, “Uhhh, like, shouldn’t that go to somebody experienced?”

J: And look what happened to Hudson Hawk!

KB: I know! Hello, Ishtar! And Hudson Hawk shot all over the world, so we were the LA office and there was a Budapest office, there was a Rome office, you know. This was 1990, so we would photocopy all the paychecks and fax them to Rome to be approved. At the time, the costume designer on that movie, and this is in 1990, was making nine thousand dollars a week. In 1990 that is a lot of money.

HEATHER: That’s a lot of money now. I’d take that. Done.

KB: Right? So you can imagine, twenty-odd years ago, I saw that, as an impressionable twenty-year old girl, and I was like, “I’m going into costumes.” Working as an assistant production coordinator was unpaid, a college-internship kind of deal. But I made friends with those people, and they took me under their wing and they said, “We’ll pay you $12 an hour, and you can come learn with us.” Like, hello. The costume designer was Marilyn Vance. She just did Bonnie and Clyde, she was Academy Award-nominated for The Untouchables, and I got to work with her and learn with her and I was like, “Man what is wrong with this? This is kind of it.” So when I graduated from school, I came to LA, sent resumes everywhere, designed for students at the AFI, and got hooked up with Roger Corman’s company.

J: As so many people have.

KB: There are only so many movies you can do for Roger Corman before you have to get the fuck out of there. I did nine movies for Roger in a year. That’s crazy. I was there from 1992-93. I started working at Corman’s company and then met people and branched out with them, and… I mean, it was a struggle, I have to say, because Roger Corman, as great as it was, like a film school, it carried with it a stigma as well. You had to battle that stigma to prove yourself.

H: You had to hustle. You are the American hustlers.

KB: Oh, honey, it is all the hustle. That is what we do. I was actually just talking about that the other night, the whole idea of how we’re such hustlers in this business. Get your hustle on. It’s crazy. And you can do the hustle well and be cool about it, or you can do the hustle and be an asshole, and I tried to be nice about it. And I can live with my decisions, you know? So, it’s been a long road. And I think back to those times at Corman, and I mean, some of my best girlfriends are chicks I met at Roger Corman in that year.

J: War buddies.

KB: Absolutely, you’re in the trenches with people. How many AM/PM hot dogs can we eat for Third Meal? By contract we’re supposed to have a break, and six hours later, a lunch, and then six hours after that, Second Meal, and then six hours after that, if they’re still going, Third Meal. There were many times when we had Third Meal working with Roger. Many times. I have a lot of stories for the burn book.

H: While we’re subliminally trying to convince you to write that book right now, let’s get into what got you to Sleepy Hollow.

KB: Yeah, that’s a good story. So, I usually work with a film director named James Wan. We’ve done four or five movies together.

H: He’s doing Fast and Furious 7, right? And he did The Conjuring.

KB: You know how you find people in your life that you work with that you love, and it’s a very special thing? I did Insidious for free, that’s how much I love him. So, he got Fast and Furious 7, and they have people that they use, so he called me a few weeks after and he was like, “I fought for you and I couldn’t get you and I’m so sorry.” I said, “It’s no big deal, I know the lady who’s done all those movies, her name is Sanja Hays, and she’s wonderful, you’re going to be well taken care of.” And about two days later, there was a Costume Designers Guild party and Sanja was there, and she looked like she was afraid I was going to come up and slap her or something. But I said, “I just want you to know, I’m so happy that you’re working with James, I told him how awesome you are, and here’s how to work with him, and you’ll be set.” And she felt so bad, and I said, “Don’t feel bad, this happens! But, I just sold my house so if you hear of anything I’d really appreciate it because now I’m kind of in a jam.” [Laughs]

So two weeks later, she calls me on the phone and she says, “I’d like to put you up for a TV show.” Sanja did the pilot but she couldn’t do the show because of Fast and Furious 7. And I’m like, “Yeah, Sanja, I’ve done TV before and I’m just… I’m not interested.” It’s a different kind of world and in my experience, it wasn’t for me. TV people are a different breed than film people. But she said this one was special, and that they are film people – they wrote Star Trek, and it’s Len Wiseman [Underworld], and she swore they were all great – and so I watched the trailer and it was Sleepy Hollow. And I was like, “Ohhh. This is a movie, really.” So I went into the meeting, and I’m a mess because by this time I’m out of my house, I don’t have any clothes, it’s horrible. I go into the meeting and there are 8 or 9 people, execs from FOX and stuff, and I sit down and they’re like, “Okay, we see you haven’t done a lot of television, why is that?” And I was like, “Well, I hate [doing] TV.” [Laughs] Because I have nothing to lose. Do I want to do this show? I don’t know, so I’m going to be honest. So I told them I don’t enjoy working on TV, but that I saw the pilot and I got what they were doing, and that it was exciting. And we talked for like 45 minutes, and then I walked out and called my agents and said, “Yeah, I told them I hated TV,” and they were like, “Well, that’s great. Let’s keep looking.” And then a week later I got the phone call.

J: They must have liked your moxie.

KB: They must have! I don’t know. I really don’t know what it was. But I did get a good feeling from them in the meeting. They weren’t the normal sleazy television people that, you know, unfortunately are sort of ubiquitous around Los Angeles. It was nice vibe, and Alex Kurtzman and Bob Orci [ed: Fringe, Alias, longtime J.J. Abrams guys] just struck me as people who I grew up with, in a way. I felt very comfortable with them and understood what they were looking for. Those guys are nuts-genius creative minds. I felt like I wanted to hug them, it was weird.

H: And so in a way, you and Sanja traded gigs.

KB: You know, she said to me that this whole situation is all about kindness and the value of kindness. And that’s so true. So Sanja and I have become much better friends through this, because she’s asking me questions about James, and I’m asking her questions about, “Where the HELL did you get that fabric, because I need more of it!”

J: What are the challenges of coming into a situation like this where someone else started the vision, and you have to carry it on?

KB: I have followed Sanja’s career for a long time and I know her aesthetic. Sanja has done Total Recall and a lot of science-fiction-y movies, she’s done XXX… There’s a sleekness and a sexiness and a seriousness about her work that is really different from mine, which is more quirky-vintage. So it has been such a stretch and such an exercise for me to get into someone else’s headspace and make decisions from that place. That’s a real challenge, but for me it’s proven to be super valuable and it’s really allowed me to stretch my wings.

H: What was the kind of prep work you had to do even before scripts started coming in? What COULD you do, without knowing what the writers were cooking?

KB: I only had four weeks of prep. We had a few outlines, so I knew what was coming down the pike, or at least I thought I knew, but of course the best laid plans… We tried to be as prepared as we possibly could. We pulled thirty-seven containers’ worth of stock from Fox, which was essentially the “look” of the show in the contemporary bits. I am a freak about the details, and I wanted to make sure that since we were portraying the New England-y version of Sleepy Hollow, that we had plenty of Barbour jackets, Fair Isle sweaters, and the like. I shuddered to think it would look “Hollywood” in that sense. We pulled with a very tight East Coast vibe in mind – – conservative, restricted color palette, et cetera. And I knew that we’d be pulling for for many of our day players from that stock, and we would need options for emergencies. I’m really happy with the way it worked out.

H: When we were on set, you mentioned some of the rules of the Sleepy Hollow costume universe, as far as color palette. What are those rules?

KB: In talking with Sanja before I started, she said, “Whatever you do, no blue.” No blue jeans, nothing. In the pilot there was no blue. Well, it’s an unfair thing to say that there was NO blue, because you saw Ichabod’s vest, it was that tealish-blue. So blue WAS used. But it was very judiciously used.

H: Why?

KB: I think this is an edict that comes from Len Wiseman [who also directed the pilot]. If you really watch the show critically, you can see what the absence of blue does to the palette of the show. It takes it into a darker place, a little bit more sinister place. Blue is a calming color, a beautiful color. But let me tell you something, when you have a lot of detectives to do and you can’t put anyone in a motherfucking blue shirt, it’s like, “FOR REAL?” I go to the store and it’s like, “Okay, what do you have in green, khaki…” There’s tan, so much tan. And yellow. It’s all we got.

H: I would think it’d be the hotter side of the color wheel they’d be worried about, like oranges.

KB: We can’t use bright orange. If we take it down, if it’s a muted or burnt pumpkin, we might be able to put that on someone. As long as it doesn’t pull focus.

H: So no neon. We will never see Abbie dressed like a hi-liter.

KB: But we can do red. Headless Horseman wears red. And incidentally, Headless Horseman is a Hessian, which is a German soldier-mercenary, and they wore a completely different uniform than the one he wears, which is a British officer’s uniform. So everyone under his command wears that, and the British officers wear red. That was something they committed to in the pilot that we are married to.

H: I feel like that has to come from red being associated with the devil, and the show’s show’s mythology that the demons infiltrated the British ranks, so you’re depicting the two sides of the war and how evil, red, was on the British side. Sorry, England.

KB: Yes, sorry about that, guys. But for audiences, it’s a whole lot easier if we codify it in that way. Because to be quite honest with you, in the Revolutionary War, there were Americans who wore red and British soldiers who wore blue, and everybody was being killed because people didn’t know what side they were on. The drummers of the regiments on the British side wore opposite colors. So if troops wore red coats with blue facings, the drummers wore blue coats with red facings, and got themselves killed time after time after time.

H: How much of this history is stuff you threw yourself into researching as you got this job? Were you conversant in historical detail before this? People forget the costumers and not just the writers are doing that work.

KB: Doing it, and sharing it. In this kind of a job environment, it is incumbent upon me to know this stuff. If I don’t, I’m not doing my job. So yeah, I have lost myself in books, and I mean ridiculous amounts of time that I should be spending doing other things, because I want to understand what it felt like to be there. Like, to get into the situation where Katrina gives her son up for adoption, I fell down the rabbit hole so hard, and you’re crying reading these stories about kids who were left thinking their parents were going to pick them up in a couple days, and of course they never were, and the parent couldn’t read or write, so the kids just had a scrap of fabric with them as the only totem of their parent. It’s fucking heartbreaking. So this show has taught me a lot. I love the research and I would do that anyway, but it’s really broadened my understanding of what life was like then, beyond just the technical details of what battle happened and who died when and who was elected. The breadth of the experience of life back then was so harsh. You could have ten kids and three would survive. That kind of thing. And as a woman, oh my God, it was a rough, rough thing.

H: There are a lot of modern comforts, like the mighty tampon, that they would have loved to have.

KB: I was thinking about that yesterday! Like, what do you do? Even in my Mom’s era, where it was hook-on belts. Disgusto! We are so fortunate to be living in the modern day of adhesives, ladies.

H: I also love that you never said the word “Wikipedia.”

KB: With Wikipedia… I mean, I taught at UCLA, and when I said to them that we’d be doing a research project, these kids brought in pictures of Mad Men. I’m like, that is NOT RESEARCH. It’s the Cliffs Notes version of research. You have to really explain to people what is legitimate research and what is not. Wikipedia in my opinion is not legitimate research.

J: What did you teach at UCLA?

KB: Costume design. For part of my class, I asked the kids to watch a movie every week and write a paper about the costumes, and interpret the costumes and tell me what they’re about. And I would empty out red sharpies all over these papers, like, “Listen guys, our job is about communication. If you cannot communicate points clearly, no one will hire you.” And I mean, I was really harsh with these kids, but they needed to know the reality. It’s not just about what you know. From a practical level, if you go to a meeting, and you can’t be direct and simple in describing your vision, no one will hire you.

H: And I’m sure Wikipedia exacerbates the issue. It’s definitely “I’m sitting at my desk taking a short cut.” Which I freely admit is what I have used it for. I think it’s fabulous that, as someone who’s busy, you still chose to take the longer road here.

KB: Well, let me tell you, it’s so addictive once you get into that kind of research because you just want more and more and more. I got Amazon Prime on this job. That’s how bad it is. I vowed I would never do Amazon Prime, and now I’m like… [mimics tapping her arm and injecting a fix].

H: What was the toughest thing you had to source?

KB: Everything, honestly. God bless Wilmington, but you cannot buy a yard of silk here. So when we’re tasked with doing something like an eighteenth-century fancy party ball, we have to call in all of our resources. We call our costume houses in England, we call costume houses in Italy, we call specialty venues in Los Angeles, we call fabric stores, we call notions people. Whatever we can do, all hands on deck. We bust our balls. And that is a challenge because it’s not just one week, it’s a LOT of weeks. Week after week, we’re trying to do this. It’s hard. It’s hard.

H: Which is tougher to find, the basic fabrics or the notions?

KB: The thing is that when we make something, usually we need multiples, and if we need multiples of a vest, a vest has twelve buttons. If we need to make four vests, at twelve buttons, that’s 50 buttons just so we have a few just to spare. I can’t buy five of the same button at JoAnn’s. Where am I supposed to get fifty? So we have our wonderful shopper in LA who helps us, in the fabric district, to source buttons. It’s just a logistical headache that we have to manage, and Steffany, the costume supervisor, is brilliant. Without her it would be very difficult to get anything done. I have a very strong team. I can’t emphasize that enough.

H: Yes, people often think of the job in the singular – “costumer.” How big is your team and how does it divvy up?

KB: There’s a union-mandated hierarchy. So it’s Costume Designer, which is me, and then Costume Supervisor, which is Steffany [Bernstein-Pratt], who takes care of the paperwork, scheduling, business angle of all of what we do. Underneath that, there’s the key costumer, who runs the truck [on-site at the main shooting location] – that person sets up for the next day, organizes everything to make sure it’s what they’re supposed to be wearing and when. And then we have set costumers, who are the ones like Julia Rusthoven, who you saw doing the fussing and fussing with each outfit. That’s how it filters down. In addition to that, we have an ager/dyer, which is also called a Breakdown Artist, that’s Julia Gombert, and then our tailor and tailoring staff, and PAs.

J: That’s a big team.

KB: We have ten people full-time and on big days we have as many as 20. It swells. Nobody in the eighteenth century could get dressed by themselves, everybody needs help, so we need…

J: They need their valets.

KB: [Affects posh accent] Yes, they need their valets. [Laughs] So it’s a huge team and I really, really fought hard to get Brad [Watson], the assistant costume designer. Because Brad and I have done five movies together over the years and he and I understand each other on a stylistic level, on a visual level… I know that if I’m not able to be there, he can be my eyes. Because his standard of what’s right is as high as mine. You cannot put a price on that. They didn’t want to bring in another person from out of town, and it’s like, “You can’t afford to? You can’t afford NOT to,” because if I’m not there because we’re shooting three units at once all over town, which has happened, I need my eyes by proxy to be on that set. And he IS my eyes. He is that person.

H: In all of this, we don’t want it to get lost that there’s someone whose job day in and day out is to touch Tom Mison.

K: Julia Rusthoven. She did the pilot, and he requested her back from the pilot. He’s loyal. You should talk to her! [Ed. Note: AND WE DID. It’s coming in Part II tomorrow.]

H: Have you ever gotten going on something you had to make/have made, or which you’ve had to search the ends of the earth to order, only to find out closer to shooting that it’s been excised from the script and you won’t need it? If so, what happens to those pieces?

KB: Yes. Oh, yes. There were early drafts of certain scripts that featured astronauts and bear suits and all kinds of nutty things. In order to be prepared, we have to pull the trigger and order those things. Later, the script changes, and the astronauts and the bear suit are gone. But by that time, of course, we already have the costumes in hand. It’s not like we can cancel or get a rebate. Once the ship has sailed, it has sailed. They basically gather sad dust at that point.

H: What’s the largest number of extras you’ve had to worry about for the show?

KB: Probably 125. In period stuff. In movies, I’ve done seven or eight hundred. But for this, 125 is a lot, and that’s just one scene. The timetable [of TV] makes everything a little bit more interesting. We are constantly prepping and shooting simultaneously. We get new draft revisions all the time. So the landscape is constantly shifting. There is a “schedule” to how we’re supposed to do things, but sometimes the things we need in place, whether it’s a script or an actor, are not in place, so we end up flying by the seat of our pants. I’m a frequent flyer at this point.

H: Are there any particularly unusual things you’ve had to as extras during casting, to be like, “We need to know this and this and this about you”?

KB: Well, it depends on the show. I’ve done a lot of shows with Native American actors, and in addition to the standards like, “What are your sizes, do you have tattoos, are you allergic to anything,” I have to ask, “Do you have any ritual scars?” And oftentimes the answer is yes. And I go, “Okay, where are they, what size are they?” Because all of that needs to be acknowledged if they’re going to have to bare their shoulders or whatever, because those scars tell a story about who the person is, so we have to be aware of that.

J: I think that’s the crux of your job – you’re telling who someone is by what they’re wearing.

KB: Thank you for stating that.

J: And this is something we talk about on the site. When an actor is in public, at a big event, they’re making a conscious decision of the story they want to tell about themselves.

KB: I talked about this a lot in a TED Talk that I did. The fact that clothing is a language, and we tell people every day who we are and what we’re about, by what we wear.

J: Sometimes what I am telling people is that I’m really tired and I haven’t had any coffee yet. But if someone’s going to the Oscars and they’re not wearing pants…

KB: Consider pants!

J: What they’re saying might be, “I have a crazy stylist and I can’t say no.”

H: But on TV it’s to the nth degree because it’s such an integral part of actual storytelling.

KB: Our job is to let the audience know who this person is before they open their mouth. It’s just that simple.

H: How do you do that with some of the characters? Like, say, Irving [the police captain, played by Orlando Jones]. It seems harder because they’re not as easily pinned down.

KB: But Irving is like that on purpose. So there you go. And that’s all I’ll say about THAT, ladies. Wink. But the crew here, the ones who’ve known me forever [from other projects], tease me about my backstories, because I put backstory into every costume that I do. Every single one.

H; So, take Irving’s daughter Macey [played by Amandla Stenberg, a.k.a. Rue in The Hunger Games]. Your backstory for her, the one that informs her visually – can come from you, or do you have to consult the writers?

KB: Nope. I do it myself, and then I will talk to them if it’s very important. I’d rather make the adjustments BEFORE I get underway than AFTER. But mostly it comes from the gut.

H: Have there ever been times when you made a backstory and the writers have come at you and said, “Well, ACTUALLY, you’ll need to change that because…”

KB: Not really. We’re getting to be pretty symbiotic, these writers and the costume department. Jose Molina, who’s written a couple of episodes, he’s a very intense and receptive collaborator in that sense and he’ll email me and say, “Okay, what should I say about this costume if I reference it in the script?” It’s a really good collaboration and it goes both ways.

H: People may think you can just go out and buy whatever’s cute right now and stick it on Amandla, but there’s always a motive behind it.

KB: It was necessary to work with Amandla’s look — her awesome curly hair, her sweet, heart-shaped face – and I needed to be careful to keep it young, bohemian, and friendly. This is, after all, a New York City girl with some style — but you don’t want to over-design her. It’s not the point of the character. This is where contemporary design gets tricky. You have to resist the urge to make it all about the costumes. Mostly, I link her visually to Jenny [Abbie’s sister] a lot, because first of all everyone’s speculating that Jenny and Irving are going to get together, which is not entirely unlike the tension that Amandla has with her dad for the fact that he’s not there all the time. So it’s all relationship tension. And also, if Irving’s not careful, Amandla will end up like Jenny. Because in episode 110 [ed: It aired last week, as 111; in production, they count the pilot as episode zero, but TV listings count it as one], Amandla has some experiences that Jenny had when Jenny was a child, that could definitely push her in that direction.

J: STAY OUT OF THE WOODS AMANDLA. Woods are never a good idea.

KB: So looking down the long road of that character, early on I decided to kind of push some of it a little, visually.

H: Let’s get into some of the other aesthetics. Ichabod’s would seem obvious, but there are probably ways you have to be careful about how you dress him, so it’d be fun to hear about how you approach it. Starting with his coat. Obviously, lots of crazy stuff happens to him in that coat. How many copies do you have?

KB: For the pilot, they made four coats. Two of them were for the revolution scenes, so they were clean, and then one of them was for post-unearthing [when Ichabod lives in present-day]. The fourth one, they had used for stunts for post-unearthing, but then they used it for the actual unearthing [from his grave], which was the last thing they needed to shoot, and so it was covered in white shit. We couldn’t keep using it like that. We had to take the one that was covered in white shit, clean it off, make it into a double for his main post-unearthing coats, and then fabricate four or five new ones to use. But the fabric didn’t exist anymore and the buttons didn’t exist anymore, and we had to source that stuff. It was… tough. But ultimately we had to do it. We didn’t have a choice.

J: He has to have a coat.

KB: He has to have a coat. We also had to make more breeches, more shirts, it was a whole thing. His boots were custom-made. We had to make four more pair of boots, and they’re like… really expensive, it’s like $1200 a pop to make the boots. So we were living with that for a while. But it’s beautiful stuff, and for what it’s worth I’m really glad, because now I know all of Sanja’s vendors. There are times when you get a good endorsement for a vendor and it doesn’t work out, but I made a lot of great new contacts on this show – I have learned a lot from some brilliant artists.

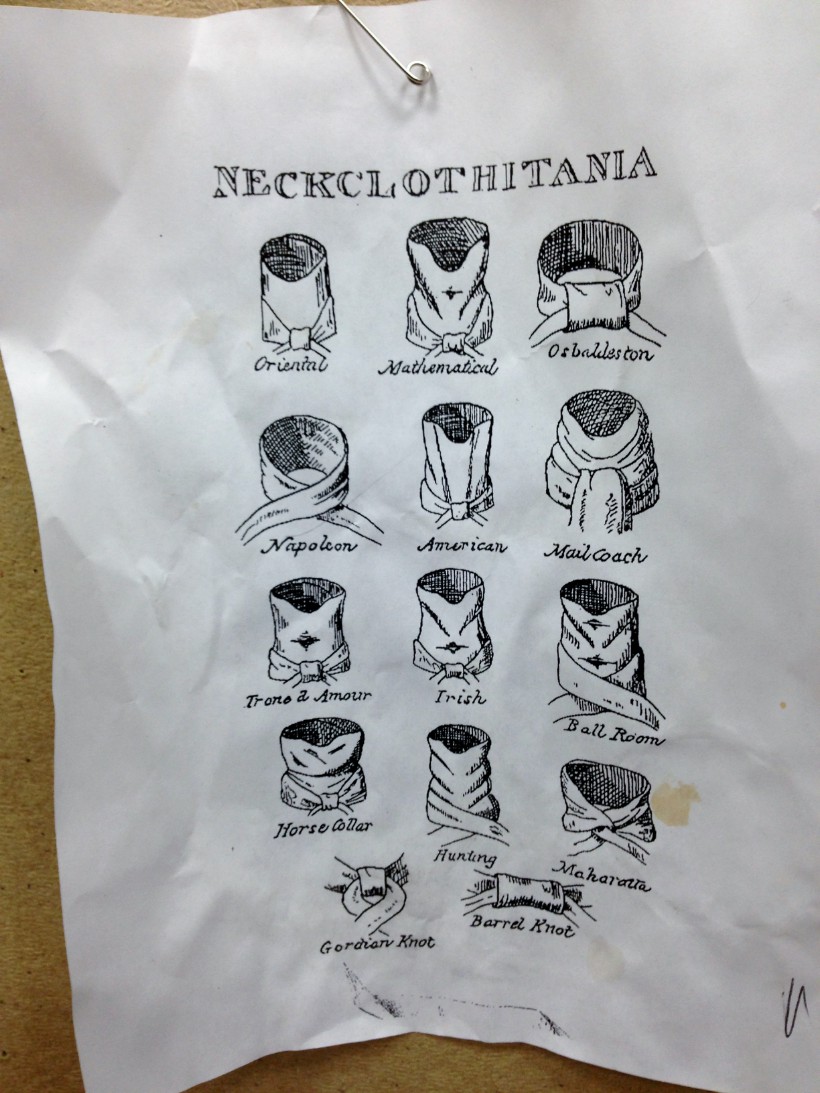

J: What about anachronisms? How careful do you have to be? For example, you can’t just choose any old fabric for Ichabod’s breeches and things.

KB: I am a serious fabric nazi. I keep a huge box of swatches under my desk, and I have a number of books about fabrics, like the history, different weaves, fibers, et cetera, that I consult when I’m feeling like we’re not hitting the mark. Because all of our fabric is sourced in LA, it’s important that Janet, our lead person there, shares with me a common language of fabric. We’ve compiled a huge fabric dictionary on this show. I will never, ever use synthetic fabrics on anyone in a period sequence. It looks cheap, and it’s unacceptable. It destroys the suspension of disbelief. I DID mention I’m a fabric nazi, right? So far I feel like our fans are SO into it, they are so forgiving, they just do not… they just want more of what we’re selling, you know? It’s amazing.

J: That’s because you did a good job in the first place.

H: And you have a hell of a salesman. You could claim he’s wearing a Revolutionary War-era fur loincloth, which is not a real thing, and people probably would be like, “Welllllll… let’s just go with it.” There’s a cool way Tom Mison [Ichabod] walks around — somehow the way he carries it, you almost believe people wouldn’t look at him on the street and think, “What the HELL is that dude wearing?” They would think, “That hot man is working that coat.”

KB: Exactly. Tom is a guy who makes everything look good. He’s in great shape. But as far as his basic stuff, his hero look, we were locked into that from the pilot. And that’s all he’s worn this season, really. Until this episode. You’ll see. Then we just kind of instinctively followed the vibe of his character. It’s hard to verbalize, but you feel it and you know what it looks like and there it is.

H: We promised we wouldn’t ask about whether you’re putting Ichabod in modern clothes, because that’s been addressed already in a few places.

KB: You’ll see how we did it. It’s clever. He’s in new clothes, but not new clothes. New to him.

J: Someone did ask us about Katrina [Katia Winter, as Ichabod’s purgatory-bound wife/witch] being a Quaker and then a society lady.

KB: Those are decisions that are made with the creative narrative landscape of this television show, of which I am not a part.

H: And it’s not like you’re calling up the writers and saying, “Hey, I know, write a ball gown scene for her, because I want to do one!” How much collaboration is there with the writers, in either direction?

KB: In this episode that we’re shooting right now, there was quite a lot of dialogue about costumes. QUITE a lot. And the writers aren’t costume historians. So I emailed them and I said, “I don’t mean to get in your business, but here’s what you said, and here’s the right way to say it,” and they corrected it. I don’t want to get in the way, but it’s my job to know that stuff.

J: How much latitude do you have with the clothes? Does everyone have to sign off on everything, or do you have freedom?

KB: My previous experience in television was this: An actor needs a necktie. I set out a table with 150 neckties, everyone comes in, and they cannot agree on one. But that doesn’t happen on this show. I told them that story in my meeting, and I said, “This is why I don’t do TV, because I can’t get a decision out of anybody,” and they were like, “Rest assured that will not happen here.” But a lot of the time, honestly, it’s like, you know what these people should look like. For example, Irving [Orlando Jones]. He has a grey suit, a darker grey suit, an EVEN DARKER grey suit, and a black suit, and a navy suit, and a textured suit, and shirts and ties. And somewhere in there, we’re going to have Irving. They’re not in my face about it, which is really nice, and something I never expected. Because my experience had been so contrary to that reality. I’m very grateful that they trust me, and that they understand that I’m there to make the show look good. I’m VERY grateful. Because not everybody who does television or film for that matter has that luxury.

H: I think in any situation, sometimes people forget you’re all on the same team.

KB: Also, sometimes, and it happens on film as well, people who are in positions of producer on some level feel the need to justify their positions, and if justifying their positions means urinating all over your department to make their mark, that’s what they will do. And that’s unfortunate.

J: When we were in reality television, there would be times you’d send in your cut and you’d get notes back, and you’d be like, “These notes are just this exec justifying having their job.”

KB: And that is a point that cannot be too strongly made. Because it’s ridiculous. [Holds up tape recorder to her mouth.] And all of us see through your shenanigans, wiseguys. I’m serious. [Laughs]

H: It’s almost amazing you haven’t had that experience on this show, because Sleepy Hollow was FOX’s first success this year.

KB: You think so?

H: It was the first pickup of the season for any network, I believe.

KB: We don’t see or hear any of this. We go to work, we come home, we sleep, we do it over again.

J: All the podcasts I listen to are obsessed with it.

KB: Bigger than The Blacklist, ladies?

J: The quality is better. Blacklist might be getting better ratings.

H: With Sleepy Hollow, fans are more immersed. They’re ‘shipping characters and pairings and enjoying the mythology. About Blacklist, I hear more people saying, “I love James Spader, but man, Megan Boone’s wig is bad.”

KB: I haven’t seen it. The girl who plays against James Spader wears a wig?

H: She has a short haircut, which I believe they are making her grow out.

J: She plays an FBI agent! She’d totally have a cute short cut.

H: And they’re all defensive about how often people make fun of this shitty, shitty wig, but the reason I think people pay so much attention to the shitty shitty wig is that the performance is not great, and so then you’re like, “Well, I don’t have a lot else to latch onto here, so my eyes are wandering to your shitty shitty wig.”

KB: Shitty Shitty Wig Wig.

H: It’s funny how that can take you out of the experience.

KB: Hair is at least 40 percent of the overall look of somebody. Hair tells you who somebody is, just as much as the costume does. If the hair is wrong, the costume is not going to work.

H: Do you do the wigs, or does hair handle that?

KB: Hair does the wigs. Ultimately we as costume designers have to oversee the look of the person because we get on the job before the hair person does, and so we have to plan before they do, and all of the stuff that we do takes longer to do than the hair. So I will send the hair department research, like, “Here’s the bus, climb on board.” We do our job a hundred percent; if [in general] any department comes in at 60 then it’ll look like shit no matter how well I’ve done my job. So we try to communicate and collaborate as much as we possibly can — it’s a team effort.

H: Like on Blacklist, there’s other work going into it that you’re not seeing, because all you can see is That Wig. But when it’s seamless, like with Ichabod, you can notice all the other things that are great about his overall look.

KB: Today was another great example. The people you saw [ed note: more on this in part two tomorrow], I hadn’t seen those wigs yet, and they worked so well, and so overall those guys looked fantastic. You want actors to feel empowered to do their best work. And when we do all the research and people — no matter who they are or what department they’re in — don’t treat the material with the same respect of level of authenticity it deserves, it can be frustrating. At some level you just have to let go. You can’t control everything, so you have to trust that it will end well, and that you’ve done your job. And I know that works in both directions.

H: You mentioned offhandedly, “I’ve done a lot of purgatory work.” Is that an actual thing? Purgatory work? What are the rules?

KB: It IS a thing! And purgatory [on Sleepy Hollow] for me is like The Further from Insidious. It’s essentially the same thing. What you’re in when you enter purgatory or The Further is what you STAY in. There is no changing of clothing. You become an avatar. Once you get in there, you’re locked into what you’re wearing.

H: So you probably have to be pretty careful what people happen to be wearing when they die. You don’t want to plan for someone to be wearing neon green or pink if they’re going to be stuck in the netherworld in it.

KB: Or anything shapeless. Yeah, all these considerations go into that decision, because, say, in Insidious, for the kid wearing his pajamas to go into The Further, he’s going to have to do stunts, all kinds of crazy shit happens, so we have to make sure what he’s wearing can accommodate stunt pads or whatever. There are a ton of practical considerations.

H: And do you try to keep them in grey, black, or white?

KB: We try to drain them of color as they are drained of life. That’s what we try to do. And anyone who enters purgatory who has life in them has a little bit more color. So, who’s NOT dead, perhaps. And certainly as in Insidious, you can’t really apply the same rules to every job, but in Insidious it’s a lot more extreme. The people who are all alive in The Further will tell you that by the colors they’re wearing.

H: Do you find yourself watching movies with a costumer’s eye? Take a movie like The Sixth Sense. Can you guess the twists by what the costumes are?

KB: I did. When I watched it, within thirty minutes I got the twist. But I mean, these are the tricks. When I watch a movie, I watch it like dailies. There’s no way for me to get over that. I can’t turn it off. As beautiful a movie as it is, watching 12 Years A Slave, all I could think about in the crowd scenes, was, “Okay, I can see these people coming out of the changing tent, getting dusted up,” and I just knew what they did to achieve that, and that’s all I could think about. It’s very distracting sometimes. An occupational hazard.

H: What are the best little tools of the trade, or magic tricks, that you can do?

KB: There are so many things. It’s just an endless list. Like a rubber band around the button that goes through the button hole that expands a collar, so that some guy who lied about his sizes can wear the shirt that we bought him that was the size he told us he was. [Laughs]

J: Never lie to a costumer.

KB: Right? I’m not sure it’s lying, really. People don’t always take their measurements that often, or it’s just wishful thinking, or they buy stuff that’s vanity sized and don’t pay attention.

H: I read a lot about people talking about interpretive costuming. Like on Scandal, Olivia is in black or white or grey, usually telegraphing her function in a scene or her emotional state. Is that a tool you use too?

KB: Absolutely. You’ll see a lot of that in Irving. When he has some big things happening, watch what his colors do, because I have planned that. Irving faces some crazy bad horrible situation that he has to reconcile, and he makes some decisions. That’s all I can say.

H: I had a follow-up question but I got all worried about Irving just now.

KB: You’ll see.

[Part two, discussing Abbie’s leather jackets, Victor Garber, Ben Franklin, and the logistics of ball gowns, can be found here.]