First and foremost, in conjunction with this profile, Elle created an online portal with resources for those suffering Intimate Partner Violence or those who want to try and help survivors. Second, if you have experienced IPV or you know someone who has, this profile may be triggering for you, so read with caution.

FKA twigs bravely went public with the details of the abuse she endured at the hands of actor Shia LaBeouf, filing a civil lawsuit against him in December — an emotional burden she was prompted to release in part, she says, out of realizing how many people might be trapped at home with their abusers during pandemic lockdowns. Writer Marion Carlos does a wonderful job with the tale, largely letting FKA twigs tell it, but interspersing it smartly with statistics about Intimate Partner Violence and observed details about twigs’ body language. It’s not in an exploitative way at all; more, it’s noteworthy the way twigs can clearly still put herself in some of those moments as she describes them. It’s telling about the psychological marks this leaves.

The story is, as you might imagine, a very emotional read, but also an important one. She is incredibly brave in her frankness. It cannot be easy to spill all the details that, while they were happening, had her shrinking back from the other people in her life out of shame (misplaced, but that’s all part of it — that’s in the abuser’s toolkit, directly or indirectly). It tackles the way abusers sweep you up in layers of microaggressions that complicate the picture when they turn into flat-out aggressions, and this lead is a preview of the details revealed therein:

“It’s a miracle I came out alive,” says FKA twigs. The British singer, born Tahliah Debrett Barnett, has spent the last hour painfully recounting the abuse she endured for nearly a year at the hands of her former boyfriend and Honey Boy costar, Shia LaBeouf. She is explaining the “calculated, systematic, tricky, and mazelike” tactics LaBeouf would use to control her—the love bombing, the gaslighting, the social isolation, the sleep deprivation. “If you put a frog in a boiling pot of water, that frog is going to jump out straightaway,” she says, attempting to explain the incremental and insidious nature of the abuse. “Whereas if you put a frog in cool water and heat it up slowly, that frog is going to boil to death. That was my experience being with [LaBeouf].”

As twigs notes, people often wonder, “If it was so bad, why not just leave?” She paints a much more complicated picture that may resonate with readers who have or who are experiencing it themselves. It it is not that simple; it is not simple, period. I won’t quote the whole thing, but I could; instead, I’ll offer up these two extra pieces:

Growing increasingly concerned for her safety, twigs began reaching out to friends for refuge. She would sometimes call in the middle of the night, saying, “I’m unsafe. Can I come to your house now?” Her friends would encourage her to come over, but as quickly as twigs would reach out for help, she would retreat, her embarrassment about the abuse overriding her fear. One friend, who wasn’t home at the time twigs contacted him, went so far as to leave his keys out for her, but she never showed up. “[My friend] was expecting me to be at his house when he got back and I just wasn’t, and then I never spoke to him again. I used to get this feeling of intense fear and shame, and I would evaporate from people’s lives.”

And:

What was also never lost on twigs was the way in which race and ethnicity compounded the abuse that was being inflicted upon her. She recalls a trip she took with LaBeouf to Jamaica, where her paternal grandparents live and she has strong ancestral ties. While staying at a luxury resort (a first for her, as the singer often stays with family in Jamaica), she befriended the staff—much to LaBeouf’s chagrin. One day, after returning from a jog around the property, LaBeouf accused her of having sex with one of the waiters; he had seen her “flip her hair” at one of them. “You don’t understand,” she said. “I’m Jamaican. These are my people. I’ve been here many times before. I’m just trying to be nice.” But LaBeouf wasn’t convinced. Twisting her politeness into betrayal, LaBeouf told twigs if she really loved him, she would avoid eye contact when ordering from male servers at the resort. “Now I realize that this is how an abuser tests your boundaries. Can he get me to look at the ground in my own island where I’m from? Yeah, he could. If he can get me to do that, how far can it go?”

There’s also a story about how, when she was trying to leave, he caught her and pinned her to the bed until she was too exhausted to go. Please read the whole piece.

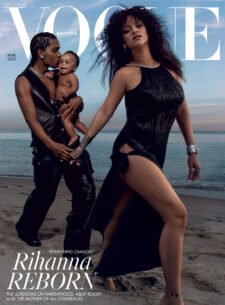

Given the seriousness of the discussion here, it felt tonally weird to segue into a discussion of the photoshoot, so the slideshow doesn’t have captions. But I will say that in the cover shot, I feel both her vulnerability and her strength, both of which she has needed to deploy in large quantities.